The Valley of Death: the Saudi Coalition is Creating a Living Nightmare for African Migrants in Yemen

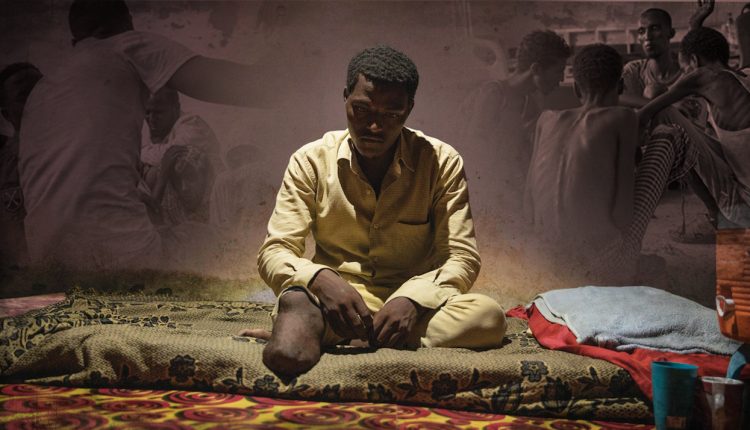

YEMEN-SAUDI BORDER — Hoping for a better life, 32-year-old Hermala left Jimma, a poor farming district in Ethiopia’s Oromia region, and set out towards Saudi Arabia. He faced unspeakable dangers along the journey, including death at sea, torture, and abuse in chasing what would ultimately remain an unfulfilled dream.

Over the course of the nearly five-year-long war in Yemen, U.S. bombs and shells in the hands of the Saudi-led coalition have not only devastated the lives of many Yemenis but have dashed the dreams of migrants from the Horn of Africa who have been stranded in Yemen’s nightmare since 2015, when the war began.

Hermala was initially hoping to emigrate to the United States, but given the Trump administration’s slew of new anti-immigrant policies, he chose instead to take his chances on a perilous journey that would see him crisscross mountains, ravines, jungles, swamps and the sea. His final destination, he hoped, would be the oil-rich Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by way of war-torn Yemen.

A combination of factors has driven hundreds of thousands like Hermala to travel through some of the most inhospitable terrain on earth in hopes of crossing the sea into war-stricken Yemen and eventually Saudi Arabia after the United States and Europe closed their doors to migrants and refugees.

This past November, Hermala traveled more than 1,000 kilometers from his home through one of the busiest maritime mixed migration routes in the world. First on buses and then later on foot, jumping the border into Djibouti, he trekked through mountains, sandstorms, and high temperatures, surviving on crumbs of bread and unclean water.

After paying his traffickers, Hermala, along with a group of seven other migrants, eventually made their way to the southern coast of Yemen on a journey that took somewhere between 12 and 20 hours through the turbulent Bab al-Mandab Strait on a severely overcrowded wooden boat. They, however, were very lucky.

The journey from the Horn of Africa to Yemen’s coast by way of the Gulf of Aden or the Red Sea is perilous. Migrants and refugees face difficult situations as smugglers sometimes force them to swim for several kilometers to avoid being captured by Saudi authorities or because the overcrowded boats are unable to traverse the turbulent waves.

Ethiopian migrants board a boat on the uninhabited coast outside the town of Obock, Djibouti, en route to Yemen, July 15, 2019. Nariman El-Mofty | AP

Another refugee in Hermala’s group told MintPress in broken Arabic that 45 of the 150 passengers aboard the boat he was on were killed when their smuggler forced them into the water after their overloaded board encountered turbulent waters off the coast of Aden.

Last July, 15 Ethiopians died after a boat off the coast of Yemen broke down and left them stranded at sea. In a refugee camp in Sana’a, survivors of another accident told MintPress that some migrants they traveled with died of hunger and thirst, while others drowned after the boats they were on were attacked. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) control Yemen’s coastal waters and carry out extensive patrols.

Despite the ongoing war and the escalating humanitarian crisis in Yemen, the past four years have seen a spike in the number of arrivals of East African refugees and migrants to Yemen. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) said that almost 90,000 East Africans, 90 percent of them Ethiopian, have arrived in Yemen since April. However, more than 150,000 migrants arrived in Yemen in 2018, a 50 percent increase from the year before.

According to IOM, between January and August of 2019, 97,069 migrants made their way to Yemen. Of those, over 13 percent were children, 66 percent of whom were unaccompanied. Overall, close to 700,000 people, mostly Ethiopians and Somalis, arrived on Yemen’s Red and Arabian seas since 2015 when the war began, according to sources in Yemen’s Immigration and Passports Department.

A journey through Hell

In Southeastern Yemen, a region under the total control of Saudi and Emirati forces, migrants face extreme risks and serious human rights violations including torture, extortion, and sexual and physical abuse. Three Ethiopians holed up in a notorious camp in Northern Yemen recounted their stories to MintPress. After nearing the end of their treacherous journeys to Yemen, they were physically assaulted by traffickers in Aden who hoped to extort ransom money from their family members in Ethiopia.

“My family sold their land to pay the ransom money,” one of the men told MintPress. Another refugee who traveled in Hermala’s group recounted how “in Lahj camp, troops beat and hung me on the wall when I refused to make a call to my relatives. They told me to call but I refused, they then beat me on my head with a stick and it was swollen and bled.” The scar was still visible on his head.

An Ethiopian migrant shows scars from torture he endured in Lahj, Yemen. Nariman El-Mofty | AP

Reports from Human Rights Watch and other groups confirm that migrants are routinely tortured and abused by traffickers and officials in Southeastern Yemen. The Saudi-led coalition and its allies have tortured, raped and executed migrants and asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa in detention centers in the port cities of Aden and Lahj, according to reports by Human Rights Watch.

The war itself brings with it its own dangers to migrants. In January, at least 30 migrants drowned when Saudi-led coalition naval vessels patrolling the Yemeni coast fired on their boat, causing it to capsize. In March 2017, a Saudi-led coalition helicopter opened fire on a vessel carrying more than 140 migrants, killing 42 Somali nationals in what Human Rights Watch called a “likely war crime.” On March 30, 2015, at least 40 refugees were killed and 200 injured when a Saudi jet targeted the Al-Mazraq refugee camp. Still, thousands of migrants that die in Yemen remain unknown, their shallow graves line the trails traversed by their countrymen still seeking a better life in a strange land.

Al-Raghwah: the valley of death

After a three month journey, Hermala and three of his travel companions finally managed to escape the clutches of traffickers in Aden only to be detained in another makeshift refugee camp run by the Saudi-led coalition. They were eventually able to escape once again, making their way from Southern Yemen north towards the Saudi border, some walking in worn-out sandals and others barefoot, exposed to the full heat of the desert sun.

The dangers faced by Hermala and other refugees traveling north are many. Migrant routes converge on Saada, where active fighting between the Yemeni resistance and Saudi forces is frequent and where hundreds are routinely killed in undiscriminating Saudi airstrikes. In Sadaa, long lines of migrants can often be seen walking as airstrikes take place nearby. Without shelter, they have no place to seek reprieve.

Although themselves facing famine, local residents provide refugees with clean water and food when possible. Through an eclectic mix of broken English and Arabic, refugees who spoke to MintPress said: “Yemenis are hospitable, they do not mind us passing through their areas or staying in them.” Others recounted how residents provided them with food and clothing and told them “the right way to Saudi Arabia.” Yemen has long been a host nation for refugees, indeed, it is the only country in the Arabian Peninsula that is a signatory to the Refugee Convention and its protocol.

African migrants walk down a highway in Marib, Yemen, July 29, 2018. Nariman El-Mofty | AP

After crossing through Yemen’s mountainous rural landscape, Hermala and 30 fellow Ethiopian refugees eventually made their way to the al-Raghwah district, a transit point to the oil-rich Kingdom near Saada. But for Hermala, whose curly hair and round face endeared him to all he encountered – even his traffickers – al-Raghwah was the last stop on his journey.

Nearly one week ago, the body of Hermala, along with three of his Ethiopian travel companions, were discovered after bombs, supplied by the United States and dropped by Saudi jets, abruptly ended their journey north. Less than a month ago, scores of Hermala’s fellow countrymen were killed in the same location when Saudi forces carried out heavy shelling on a busy marketplace.

The attack came nearly a week after ten African refugees were killed and 35 wounded after Saudi border guards lobbed mortar shells into a bustling congregating point for African refugees on the Saudi-Yemen border. Migrants describe the area as the valley of death as the smell of gunpowder and dead bodies often lingers in the air.

Nearly every day migrants who have managed to travel across continents, stave off death by sea, disease and hunger, succumb to death thanks to a seemingly endless supply of weapons provided to the Saudi-led coalition by the United States.

Yemen’s al-Raghwah border area, located in the Munabbih district of Saada, is dotted with camps inhabited by thousands of migrants from Ethiopia and Somalia hoping to cross the border into wealthy Saudi Arabia.

Most of Yemen’s border areas with Saudi Arabia have been rendered little more than burning battlefields where Saudi forces are pitted against Yemen’s resistance led by the Houthis. For the most part, though, those fires have not yet reached al-Raghwah. Al-Raghwah is almost solely populated by Ethiopian and Somali refugees, who, for the most part, run the myriad refugee camps in the area. The Saudi-led coalition has long described the area as a known smuggling zone but has only recently identified it as an active military zone.

Even for those migrants who have died, there is no reprieve. There are not enough graves for the dead whose bodies wither, contaminating food and water supplies. The bodies of migrants shot by Saudi border guards while attempting to cross the border are seldom removed, serving as a morbid warning to others who dare make the attempt.

In al-Raghwah, everyone has a tragic story to tell. Dopamine is in seemingly shorter supply than food and water. One remarkable girl, whose smile seems never to leave her ashen face, however, seems to be an exception to al-Raghwah’s grim reality. She used to work as a nurse in Ethiopia and left her family hoping to find work in Saudi Arabia so that she could support her sister and elderly father. She now spends her time scurrying between sick and injured patients in the camp, using her skills, and very limited resources, to help who she can.

She speaks broken Arabic, most of the other refugees in the camp cannot speak it at all, and tells MintPress, “nothing [in the camp] scares me anymore except for the whiz of flying jets and the sound of the bombs when they hit the ground.” She explained how she screams and lies down every time she hears an airplane. “The place here becomes terrifying.”

An Ethiopian migrant outside a lockup in Ras al-Ara, Lahj, Yemen, July 25, 2019. Nariman El-Mofty | AP

Many migrants in al-Raghwah suffer from severe physical and mental health challenges resulting from their experiences on their journeys, their time in southern Yemen’s detention camps and a fear of being killed or worse, returning home empty handed.

Despite the thousands of migrants in al-Raghwah, there is no health center or sanitation system here, and epidemics are widespread. Somewhere between three and five people die every day from cholera, malaria and other diseases.

The final destination

Under the cover of darkness, many migrants try to sneak into Saudi Arabia from nearby al-Thabit. By sunrise, dead bodies litter the crossing routes. Only a few lucky ones make into the Kingdom to earn their livings as servants or laborers.

One wounded migrant told MintPress that Saudi border guards shot her without warning while she was attempting to cross the border in al-Zamah, three kilometers away from al-Raghwah. She described the scene at the border: “warplanes did not leave the sky, bombs were dropped constantly, there was no place to take cover. There were so many dead people at the border. You could walk on the corpses.”

Edris, Nebiyu, and Dina, all migrants from Ethiopia, said that an Apache helicopter fired at them as they were walking on foot through al-Thabit. “Everyone scattered. People fleeing were shot, many were killed or injured,” Edris recounted. His friend was shot in the head and killed, they left him on the ground and fled.

For its part, the International Organization for Migration has expressed alarm over the death of migrants in the area.

Some migrants, unable to cross the border and unwilling to face the inhumane treatment in refugee camps or detention centers, are beginning to return home. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the IOM announced that 5,087 Somali refugees have returned home from Yemen since 2017.

Martin Manteaw, UNHCR’s Deputy Representative in Yemen said that “Some refugees are now opting to return home and it is important for UNHCR to continue to help those voluntarily wishing to go home to do so in dignity and safety.”

Hermala’s friends, still stranded in al-Raghwah’s nightmare, have not yet crossed the border, nor are they considering returning home. Their desperation spurs them on to risk their lives, no matter the odds.

Feature photo | Photos by the Associated Press, Graphic by Claudio Cabrerra for MintPress News

Ahmed AbdulKareem is a Yemeni journalist. He covers the war in Yemen for MintPress News as well as local Yemeni media.